Gaussian curvature

In differential geometry, the Gaussian curvature or Gauss curvature of a point on a surface is the product of the principal curvatures, κ1 and κ2, of the given point. It is an intrinsic measure of curvature, i.e., its value depends only on how distances are measured on the surface, not on the way it is isometrically embedded in space. This result is the content of Gauss's Theorema egregium.

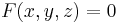

Symbolically, the Gaussian curvature Κ is defined as

.

.

where  and

and  are the principal curvatures.

are the principal curvatures.

Contents |

Alternative definitions

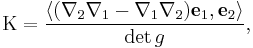

It is also given by

where  is the covariant derivative and g is the metric tensor.

is the covariant derivative and g is the metric tensor.

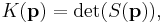

At a point p on a regular surface in R3, the Gaussian curvature is also given by

where S is the shape operator.

A useful formula for the Gaussian curvature is Liouville's equation in terms of the Laplacian in isothermal coordinates.

Informal definition

We represent the surface by the implicit function theorem as the graph of a function, f, of two variables, in such a way that the point p is a critical point, i.e., the gradient of f vanishes (this can always be attained by a suitable rigid motion). Then the Gaussian curvature of the surface at p is the determinant of the Hessian matrix of f (being the product of the eigenvalues of the Hessian). (Recall that the Hessian is the 2-by-2 matrix of second derivatives.) This definition allows one immediately to grasp the distinction between cup/cap versus saddle point.

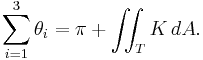

Total curvature

The surface integral of the Gaussian curvature over some region of a surface is called the total curvature. The total curvature of a geodesic triangle equals the deviation of the sum of its angles from  . The sum of the angles of a triangle on a surface of positive curvature will exceed

. The sum of the angles of a triangle on a surface of positive curvature will exceed  , while the sum of the angles of a triangle on a surface of negative curvature will be less than

, while the sum of the angles of a triangle on a surface of negative curvature will be less than  . On a surface of zero curvature, such as the Euclidean plane, the angles will sum to precisely

. On a surface of zero curvature, such as the Euclidean plane, the angles will sum to precisely  .

.

A more general result is the Gauss–Bonnet theorem.

Important theorems

Theorema egregium

Gauss's Theorema Egregium (Latin: "remarkable theorem") states that Gaussian curvature of a surface can be determined from the measurements of length on the surface itself. In fact, it can be found given the full knowledge of the first fundamental form and expressed via the first fundamental form and its partial derivatives of first and second order. Equivalently, the determinant of the second fundamental form of a surface in R3 can be so expressed. The "remarkable", and surprising, feature of this theorem is that although the definition of the Gaussian curvature of a surface S in R3 certainly depends on the way in which the surface is located in space, the end result, the Gaussian curvature itself, is determined by the inner metric of the surface without any further reference to the ambient space: it is an intrinsic invariant. In particular, the Gaussian curvature is invariant under isometric deformations of the surface.

In contemporary differential geometry, a "surface", viewed abstractly, is a two-dimensional differentiable manifold. To connect this point of view with the classical theory of surfaces, such an abstract surface is embedded into R3 and endowed with the Riemannian metric given by the first fundamental form. Suppose that the image of the embedding is a surface S in R3. A local isometry is a diffeomorphism f: U → V between open regions of R3 whose restriction to S ∩ U is an isometry onto its image. Theorema Egregium is then stated as follows:

- The Gaussian curvature of an embedded smooth surface in R3 is invariant under the local isometries.

For example, the Gaussian curvature of a cylindrical tube is zero, the same as for the "unrolled" tube (which is flat).[1] On the other hand, since a sphere of radius R has constant positive curvature R−2 and a flat plane has constant curvature 0, these two surfaces are not isometric, even locally. Thus any planar representation of even a part of a sphere must distort the distances. Therefore, no cartographic projection is perfect.

Gauss–Bonnet theorem

The Gauss-Bonnet theorem links the total curvature of a surface to its Euler characteristic and provides an important link between local geometric properties and global topological properties.

Surfaces of constant curvature

- Minding's theorem (1839) states that all surfaces with the same constant curvature K are locally isometric. A consequence of Minding's theorem is that any surface whose curvature is identically zero can be constructed by bending some plane region. Such surfaces are called developable surfaces. Minding also raised the question whether a closed surface with constant positive curvature is necessarily rigid.

- Liebmann's theorem (1900) answered Minding's question. The only regular (of class C2) closed surfaces in R3 with constant positive Gaussian curvature are spheres.[2]

- Hilbert's theorem (1901) states that there exists no complete analytic (class Cω) regular surface in R3 of constant negative Gaussian curvature. In fact, the conclusion also holds for surfaces of class C2 immersed in R3, but breaks down for C1-surfaces. The pseudosphere has constant negative Gaussian curvature except at its singular cusp.[3]

Alternative Formulas

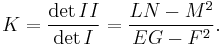

- Gaussian curvature of a surface in R3 can be expressed as the ratio of the determinants of the second and first fundamental forms:

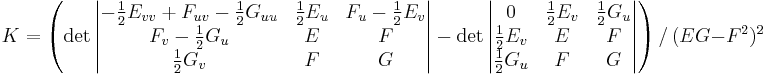

- The Brioschi formula gives Gaussian curvature solely in terms of the first fundamental form:

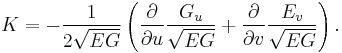

- For an orthogonal parametrization, Gaussian curvature is:

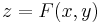

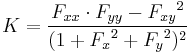

- For a surface described as graph of a function

, Gaussian curvature is:

, Gaussian curvature is:

- For a surface

, Gaussian curvature is:[4]

, Gaussian curvature is:[4]

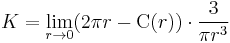

- Gaussian curvature is the limiting difference between the circumference of a geodesic circle and a circle in the plane[5]:

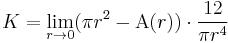

- Gaussian curvature is the limiting difference between the area of a geodesic disk and a disk in the plane[5]:

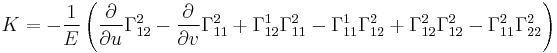

- Gaussian curvature may be expressed with the Christoffel symbols:[6]

External links

References

- ^ Porteous, I. R., Geometric Differentiation. Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 0-521-39063-X

- ^ Kühnel, Wolfgang (2006). Differential Geometry: Curves - Surfaces - Manifolds. American Mathematical Society. ISBN 0821839888.

- ^ Hilbert theorem. Springer Online Reference Works.

- ^ Gaussian Curvature on Wolfram MathWorld

- ^ a b Bertrand–Diquet–Puiseux theorem

- ^ Struik, Dirk (1988). Lectures on Classical Differential Geometry. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0486656098.

See also

|

||||||||||||||

![K=\frac{[F_z(F_{xx}F_z-2F_xF_{xz})%2BF_x^2F_{zz}][F_z(F_{yy}F_z-2F_yF_{yz})%2BF_y^2F_{zz}]-[F_z(-F_xF_{yz}%2BF_{xy}F_z-F_{xz}F_y)%2BF_xF_yF_{zz}]^2}{F_z^2(F_x^2%2BF_y^2%2BF_z^2)^2}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2b336727f40e8f9168f269daa89e6018.png)